A success story: With over 150,000 contributions, citizen scientists help protecting wild rivers

Wild rivers provide habitat for a wide variety of plant and animal species and play a vital role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. Due to the increasing pressure of human activities, wild rivers are disappearing at an extremely fast rate globally. The Citizen Science project "Wild River" aims to counteract this trend. Researcher Shuo Zong tells us how the project intends to achieve this, what it is all about and why it is already a great success.

Author: Ursina Roffler

The interview was conducted in writing and in English.

Ursina Roffler: Mr. Shuo Zong, can you briefly summarize what the Citizen Science project "Wild River" is about, how citizen scientists are involved in it and how it intends to contribute to a better protection of rivers?

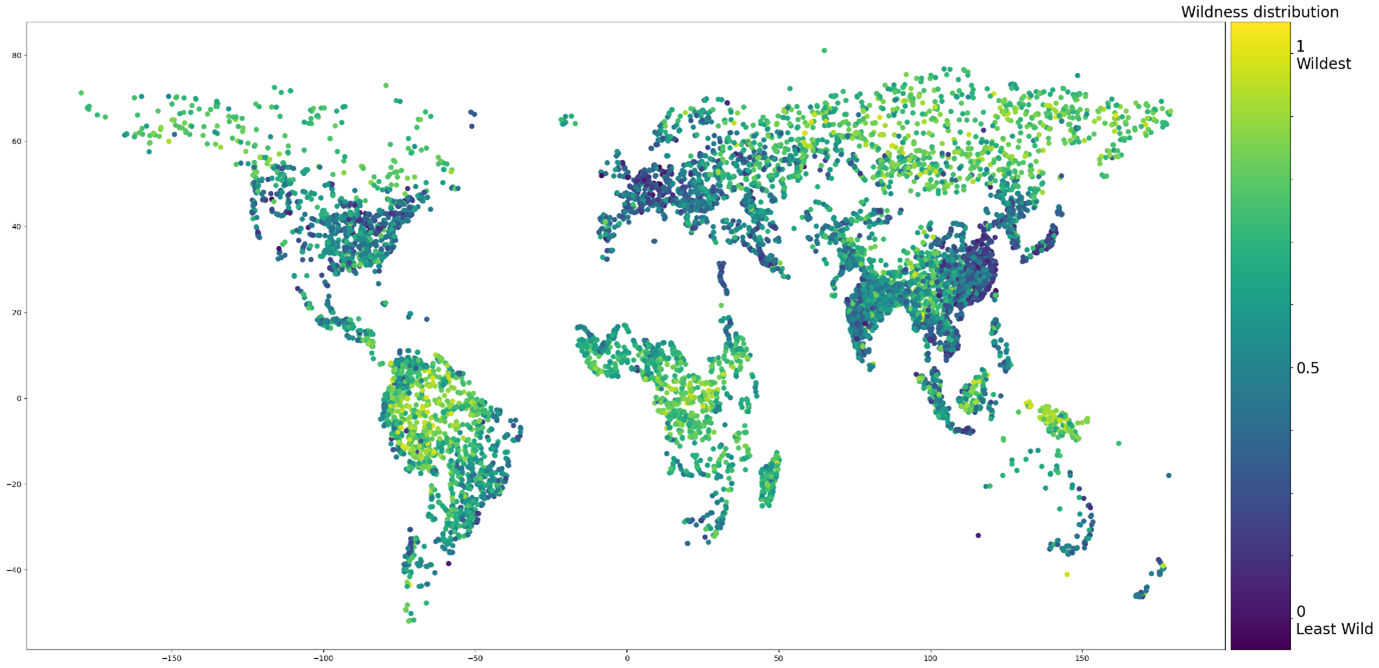

Shuo Zong: The "Wild River" project is a Citizen Science project that leverages crowd intelligence, artificial intelligence, and satellite imagery to assess the wildness of large rivers worldwide. Our goal is to create a comprehensive inventory map of global large rivers, highlighting their current state of wildness. Citizen scientists play a crucial role in this project by participating in a simple yet effective process: they're presented with two river images and asked to choose which one is wilder. Through numerous pairwise comparisons, our ranking algorithm assigns a wildness score to each image. This innovative tool enables us to identify river sections that are still pristine and worthy of protection, as well as those that are heavily disturbed. The resulting map will provide invaluable insights for conservation efforts, informing targeted actions to safeguard and restore remaining wild and semi-wild rivers and monitor the trajectories of rivers globally. Moreover, we may uncover surprisingly disturbed rivers in previously thought-to-be-pristine environments, such as some places in South America and Africa, where mining, deforestation, and urbanization have had a significant impact. This knowledge will help us prioritize our river conservation strategy and take effective action to protect these vital ecosystems.

The participation was a great success – over 150,000 contributions came together within only 12 weeks, congratulations! Do you have any tips and tricks for other projects on how to motivate participants to take part so enthusiastically?

Sure, it was hard in the beginning, because we need to make many out-reaches to make people aware of it. Fortunately, a colleague from France who had experience with similar Citizen Science projects on coral reefs was able to share his network of enthusiastic citizen scientists, which was a huge help.

We also found that hosting interactive sessions, such as in-person or even zoom sessions, was crucial in demonstrating how the project works. This approach helped people understand the project and sparked their interest, encouraging them to participate again when they had the opportunity. Our project's digital labelling nature meant that physical involvement wasn't necessary, but the interactive sessions still made a significant difference.

There are additional strategies we could have employed to boost participation, such as creating a competitive campaign with small prizes. I believe this approach would have motivated participants even further. However, we would also need to have more careful quality control.

What are the first findings of the study?

By applying our ranking algorithm to the Citizen Science answering records, we were able to assign a wildness value to each river image. We then mapped these locations and compared the wildness values to high-resolution satellite images. The results were intuitively consistent and reasonable, and we also cross-checked them against current land cover layer and human activity layer from current available dataset. Interestingly, we found that there was limited overlap between our wildness values and these existing datasets, particularly in semi-wild and wild regions. Moreover, our analysis revealed a concerning trend: in many locations across Australia, South America and Africa, the condition of rivers is not good anymore due to human activities such as agriculture and mining, as illustrated on the map below. These findings have raised significant concerns and underscore the need for targeted conservation efforts.

What are the next steps in the project? How will it continue?

We now trained a deep learning model based on this unique dataset thanks to our citizen scientists. We have already seen the model performed very well based on the model evaluation. We will keep optimizing the model, once the model is ready, we will predict across all the large rivers in the globe to have an inventory map of wild river. We can also predict backwards 5-10 years with satellite image to see which rivers changed massively in the past few years.

The project runs on the Project Builder – one of the Digital Tools that Citizen Science Zurich provides to analyse data. Why did you decide to use the tool and what experiences have you had with it?

The Project Builder from Citizen Science Zurich is really a great tool, very handy, which has proven to be an invaluable tool for my project. Initially, I was searching for a platform that could accommodate a ranking task, but most Citizen Science platforms only offered tasks such as image labelling and object selection for vision tasks.

I was delighted to discover that Citizen Science Zurich could tailor the task to my specific needs through the Project Builder framework. In general, it’s easy for participants to use, which is essential for encouraging broader participation and engagement. I also had some technique issues with the tool when there are many citizen scientists contributing at the same time.

What highlights and insights do you personally take away from the project?

Using crowd intelligence (Citizen Science) coupled with artificial intelligence is a great way to make conservation efforts, there is a great opportunity and potential to discover. We can apply similar approaches to other conservation efforts with Citizen Science, machine learning and remote sensing.

Finding the right target group of citizen scientists was also crucial to our project, meaning the participants have the right capabilities and enough motivation to participate in the project.

Thank you very much for the interview.

About Shuo Zong: Shuo has a strong passion for meandering rivers, canyons, and estuary landscapes. He loves exploring and photographing these natural wonders. He is a now PhD student in fluvial biodiversity monitoring with environmental DNA, remote sensing and machine leaning at D-USYS ETH Zurich.